We’re very pleased to at last be bringing you a blog post from a French Canadian contributor, self-represented litigant Yves Montplaisir; see below for an English translation, provided by NSRLP RA Kelsey Buchmayer.

Le Citoyen Non Représenté A-T-Il Droit À La Justice Civile En Dehors De La Cour Des Petites Créances De Sa Province?

par Yves Montplaisir, PNR

Je me décrirais comme un citoyen relativement chanceux malgré les importants problèmes et difficultés rencontrés depuis dix ans. J’ai deux merveilleux enfants à qui j’aimerais léguer une société où ils pourront obtenir justice, même si ils doivent pour ce faire, se représenter seuls devant un juge. Heureusement, nous sommes probablement parmi les rares habitants de cette planète pour qui ce rêve est possible. C’est pourquoi je crois qu’il est de notre devoir, pour les générations futures, d’y voir dès maintenant!

Le présent texte se veut une description des leçons que j’ai apprises suite à mon expérience que j’ai vécu à la Cour supérieure, à la Cour d’appel du Québec ainsi qu’à la Cour suprême du Canada dans deux dossiers en particuliers de responsabilité professionnelle et civile.

Le premier dossier (# 500-17-091770-159) est celui qui m’oppose à ma Caisse populaire Desjardins, à mon ancien notaire personnel ainsi que six agences de courtage immobilier. Le deuxième dossier, (#500-17-097489-176), m’oppose également à un courtier immobilier et à son agence immobilière ainsi qu’à un notaire. Il est important de noter que les avocats représentant les notaires et les courtiers sont les mêmes dans les deux dossiers puisqu’ils sont payés par le Fonds d’assurance responsabilité professionnelle du courtage immobilier du Québec (FARCIQ) pour les courtiers et par le Fonds d’assurance-responsabilité professionnelle de la Chambre des notaires du Québec (FARPCNQ) pour les notaires.

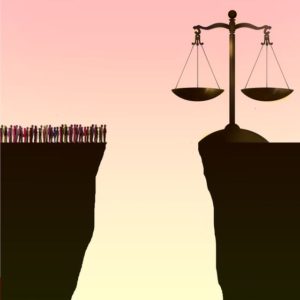

Un état de droit pour tous?

Le titre de cet article sous-entend une question : Vivons-nous dans une société où l’état de droit en matière civile existe pour tous les citoyens sans avocats ou seulement pour les plus riches de notre société représentée par des avocats richement payés?

Le titre de cet article sous-entend une question : Vivons-nous dans une société où l’état de droit en matière civile existe pour tous les citoyens sans avocats ou seulement pour les plus riches de notre société représentée par des avocats richement payés?

Avant le jugement du 17 juillet 2017 accueillant la requête en rejet de ma Caisse populaire Desjardins et de mon ancien notaire, je croyais, un peu comme tout le monde dans notre société démocratique, avoir le droit, en vertu de la Loi, d’entreprendre moi-même des procédures en justice civile sans avocats.

Je croyais que tous les juges, lors des audiences, étaient impartiaux, équitables, attentifs et sensibles aux conséquences d’abus ou de fautes dont je pourrais avoir été victime de la part d’un tiers. Je croyais aussi que les juges s’assureraient de compenser les inconvénients procéduraux issus de la méconnaissance des procédures par un PNR, comme moi, afin de maintenir l’équilibre des forces entre les parties afin d’assurer un débat loyal permettant de faire ressortir la vérité ainsi que le droit qui en découle. Je croyais qu’un juge tiendrait compte des contraintes que je vivrais à ce moment afin que je puisse avoir le temps requis pour bien faire valoir mes droits et représenter mes intérêts.

Or à l’exception de quelques juges, ce n’est malheureusement pas l’expérience que j’ai vécu jusqu’à maintenant à la Cour supérieure, à la Cour d’appel du Québec et même à la Cour suprême du Canada et je suis donc obligé de répondre non à cette question. En conséquence de quoi même s’il vit dans un état de droit, le PNR du Québec ne peut en pratique exercer son droit à la justice civile dans les cours supérieures de justice actuelles.

Qui sont les juges et d’où viennent-ils?

Je me suis aussi rendu compte que ces juges sont principalement d’anciens avocats provenant pour la plupart de grands bureaux d’avocats où ils étaient payés à grand frais, au moins 200000$/an,par des clients multimillionnaires si non milliardaires et que j’attaquais en fait le genre de clients qui leurs avaient permis de s’enrichir.

Et finalement qu’en tant que PNR, j’engageais des procédures judiciaires qu’à leurs avis seuls des avocats avaient une chance raisonnable de réussir et que seuls des avocats, comme eux, devraient avoir le droit de faire. Par conséquent, donner raison à un PNR c’est avouer qu’il n’est pas nécessaire pour gagner d’avoir les compétences d’un avocat dénigrant par le fait même la valeur de ses propres compétences comme juriste. En conséquence de quoi compte tenu de ces préjugés et conflits d’intérêt des juges, il devient donc impossible en pratique, pour un PNR comme moi et ce dès le départ, d’avoir quelques chances de succès.

En plus en tant que PNR s’ils me donnaient gain de cause en m’accordant des millions de dollars en dommages sans avoir été obligé d’engager un avocat, qu’adviendrait-il alors des avocats et de la valeur des honoraires élevés devant une armée de PNR dans les cours de justice pour réclamer, comme moi, le respect de leurs droits?

Comment les avocats des grands bureaux d’avocats pourraient-ils alors convaincre leurs richissimes clients de leurs payer des honoraires exorbitants s’ils ne peuvent pas leurs garantir qu’ils n’auront rien à payer même s’ils ont commis la pire des fautes à l’encontre d’un PNR?

Comment pourraient-ils alors être certain de pouvoir être en mesure de pouvoir donner cette garantie sans être certain que la majorité des juges, issus des mêmes grands bureaux d’avocats qu’eux, n’accorderont pas des dommages importants à un PNR?

Les avocats de ces grands bureaux d’avocat en devenant juge dans les Cours supérieures amènent avec eux la culture juridique et les préjugés de ceux-ci à l’endroit des PNR et surtout le désir de ne rien changer aux systèmes de justice actuels qui les servent si bien. C’est la seule explication logique, que j’ai trouvé, susceptible d’expliquer les comportements et les décisions de certains des juges que j’ai rencontré dans mes dossiers. Ainsi, les avocats qu’ils soient plaideurs ou juges sont en conflit d’intérêt lorsque vient le temps d’allouer des moyens et du soutien aux PNR parce que ces derniers sont vus comme des concurrents qui menacent la profitabilité de leur profession et leur contrôle exclusif du système de justice.

L’arrêt PINTEA c. Johns permet-il l’encadrement du pouvoir discrétionnaire des juges?

Mon expérience dans les cours de justice du Québec m’a permis de me rendre compte que le pouvoir discrétionnaire des juges pouvait être exercé d’une façon tout à fait arbitraire et ce, sans logique face aux faits, aux preuves présentées, aux lois et aux jurisprudences invoquées par un plaideur non représenté (PNR).

C’est la raison pour laquelle j’étais très heureux lorsque la Cour suprême du Canada est venue encadrer l’exercice de ce pouvoir discrétionnaire en souscrivant, dans l’arrêt PINTEA c. John du 18 avril 2017, aux principes décrient dans le document du Conseil canadien de la magistrature Énoncé de principes concernant les plaideurs et les accusés non représentés par un avocat élaborés en 2006:

- FAVORISER LE DROIT D’ACCÈSen s’assurant que tous les PNR puissent comprendre et présenter efficacementleur cause en ayant droit à des processus judiciaires ouverts, transparents, clairement définis, simples, commodes,efficaces, faciles à comprendre et que les PNR aient unsoutien à l’auto assistance adéquat, qu’ils soient informer des conséquences et des responsabilités qu’impliquent l’absence d’un avocat et qu’ils soient dirigés vers d’autres sourcesappropriées d’information, d’éducation, de conseil et d’assistance;

- FAVORISER L’ÉGALITÉ DE LA JUSTICE en s’assurant que toutes les PNR, aient égalité d’accès au système judiciaire où le processus judiciaire est équitable et impartial, où les PNR ne sont pas injustement défavorisées, où les PNR ne sont pas empêchées d’obtenir réparationparce que la présentation de leur cause comporte un défaut mineur ou facile à corriger, où les juges emploient des mesures de gestion des instances, selon les besoins, afin de protéger les droits et les intérêts des PNR, où les juges doivent employer des mesures non préjudiciables et positives de gestion des instances et de salle d’audience, afin de protéger le droit égal des parties de se faire entendre;

- S’ASSURER QUE TOUS LES PARTICIPANTS DU SYSTÈME JUDICIAIRE, tels que les juges, les avocats, les administrateurs, les autres participants au système judiciaire ainsi que les PNR, assument leurs responsabilitésenvers les procédures engagées par les PNR.

Ainsi tous les systèmes de justice du Canada et tous ses juges, lorsqu’une des parties est un PNR, doivent appliquer ces principes. À ces principes, qui doivent être appliqués lorsque l’une des parties est un PNR, s’ajoutent les principes s’appliquant à toutes les parties et édictées également par le Conseil canadien de la magistrature dans Code de déontologie judiciaireélaborés en 1988 soient l’indépendance de la magistrature, l’intégrité, la diligence, l’égalité et l’impartialité.

Quels sont les indicateurs susceptibles de nous permettre d’évaluer si un juge respecte lors d’une audience ou dans son jugement les principes auxquels souscrit la Cour suprême du Canada dans l’arrêt PINTEA c. Johns?

Il y a, entre autres selon mon expérience, certaines questions qui peuvent indiquer si les principes, auxquels la cour suprême a souscrit, sont respectés lors d’une audience ou dans un jugement lorsqu’un pnr est présent :

- Est-ce que le juge a questionné le PNR au sujet des à priori ou des raisons ou des faits susceptibles d’influencer son jugement ?

- Est-ce, qu’avant de rendre jugement, le juge a décrit son raisonnement d’une façon détaillée et transparente au PNR ?

- Est-ce, qu’avant de rendre jugement, le juge explique au PNR pourquoi il prévoit retenir certains motifs pour l’élaboration de son jugement ?

- Est-ce qu’il y a eu une possibilité raisonnable pour le PNR de corriger les erreurs de raisonnement et de faits intervenant dans la logique du raisonnement du juge ?

- Est-ce qu’il y a présence, dans le raisonnement du juge, de l’évaluation des facteurs légaux (Chartes, Lois, jurisprudences, etc.…) pouvant être favorables au dossier du PNR et témoignant de l’évaluation de la balance des probabilités ?

- Est-ce qu’il y a eu une possibilité raisonnable pour le PNR de pouvoir se préparer et réagir efficacement aux motifs retenus par le juge avant que celui-ci ne rende jugement ?

- Est-ce qu’il y a eu un accommodement d’offert au PNR afin qu’il puisse avoir plus de temps pour trouver un expert puisqu’il est très rare qu’un expert accepte un mandat lorsqu’il n’a pas d’avocat pas au dossier ?

- Est-ce que le juge a évalué, lorsque le PNR ne réussit pas à trouver l’expert qu’il recherche dans le délai prévu, la possibilité d’imposer un expert commun afin de faire ressortir la vérité et le droit qui en découle ?

- Est-ce que le juge a lu et examiné tous les documents et preuves soumis par le PNR ?

- Est-ce que le juge a fourni au PNR l’assistance additionnelle requise et adaptée à ses contraintes médicale, familiale, professionnelle, juridique, etc. qui limitent ses possibilités d’action ?

- Est-ce que le juge, lorsqu’il constate une faiblesse dans le dossier du PNR, lui a permis de corriger cette faiblesse ou une erreur de procédure ?

- Est-ce que le juge a fixé des délais qui respectent les contraintes du PNR ?

- Est-ce que le juge s’est assuré, tout au long des procédures, que les avocats des parties adverses n’ont pas induit en erreur ou trompé le PNR et ce, surtout lorsqu’il s’apprête à prendre une décision défavorable au PNR ?

- Est-ce que le juge s’assure que les avocats des parties adverses assument correctement leurs obligations envers le PNR en tant qu’officier de justice ?

- Est-ce que le juge s’assure que les avocats des parties adverses respectent correctement leurs obligations déontologiques envers le PNR ?

- Est-ce que le juge s’est assuré que le PNR bénéficie véritablement un débat loyal et complet ?

- Est-ce que le juge a interrogé le PNR pour qu’il puisse évaluer la pertinence d’éventuels motifs de jugement favorables et défavorables au PNR susceptibles d’être utilisés dans son jugement ?

Ces questions sont particulièrement pertinentes lorsqu’il s’agit de comparer et comprendre deux jugements de même nature impliquant un même PNR avec deux résultats opposés.

C’est de cette façon que j’ai découvert ces indicateurs, sous forme de questions, lorsque j’ai cherché à comprendre pourquoi, d’un côté je n’avais pas réussi à empêcher l’acceptation, par la juge de première instance, d’une requête en irrecevabilité dans un dossier demandée par ma Caisse populaire Desjardins et le Fonds d’assurance responsabilité des notaires du Québec (où le Fonds d’assurance responsabilité des courtiers immobiliers était mis en cause) et de l’autre, le refus d’une même requête en irrecevabilité par un autre juge de première instance de la même Cour supérieure dans un autre dossier complémentaire où les autres parties sont également le Fonds d’assurance responsabilité des notaires du Québec et le Fonds d’assurance responsabilité des courtiers immobiliers.

Évidemment ces indicateurs ne sont pas exhaustifs et il y a surement plusieurs autres qui n’y sont pas mentionnés. C’est la raison pour laquelle j’avais demandé, dans ma réplique à la Cour suprême du Canada, de bien vouloir confirmer ou infirmer ces indicateurs et d’en définir d’autres au besoin afin que tous les PNR du Canada puissent avoir un outils d’évaluation simple et efficace pour déterminer si un juge respecte ou non les principes qu’elle a entériné dans l’arrêt PINTEA c. John et ainsi mettre fin définitivement aux comportements et décisions arbitraires et discriminatoires de certains juges envers les PNR.

Malheureusement, la Cour suprême du Canada a refusé de faire respecter les principes, qu’elle a entériné dans l’arrêt PINTEA c. Johns. Elle a refusé ma demande d’appel dans un dossier où pourtant les preuves du non-respect de ces principes, de discrimination et de fabulation de la part de la première juge de première instance de la Cour supérieure sont nombreuses et claires et qu’en plus la Cour d’appel du Québec a refusé à deux reprises de corriger, les PNR du Québec ont raison de douter de la capacité d’un grand nombre de juges de pouvoir rendre justice à un PNR.

Comment garantir le respect des droits des PNR?

Si les cours actuelles sont majoritairement hostiles à faire respecter les droits et intérêts des PNR, qui a le pouvoir et le devoir de corriger la situation et de s’assurer que les droits et intérêts des PNR puissent être respectés et défendus en tout temps?

Qui a le pouvoir et l’obligation de nommer ces juges des cours supérieures et de définir les critères de nomination de manière à ce que les droits et intérêts des PNR soient respectés?

Qui a le pouvoir et l’obligation de s’assurer et d’évaluer si les juges respectent leurs obligations envers les PNR?

Qui a le pouvoir et l’obligation de former de façon continue des juges à l’égard de la façon d’intervenir équitablement auprès d’un PNR?

Qui a le pouvoir et l’obligation d’évaluer périodiquement le respect des principes et des règles déontologiques que tous les intervenants du système judiciaire doivent appliquer en présence d’un PNR?

Qui a le pouvoir et l’obligation de corriger les comportements des intervenants ou des tribunaux du système judiciaire susceptibles de ne pas respecter les principes et des règles déontologiques qu’ils doivent appliquer en présence d’un PNR?

Les réponses à ces questions nous indiquent que les gouvernements du Canada et du Québec ont la responsabilité ultime de s’assurer que les principes énumérés par le Conseil canadien de la magistrature en 2006 soient appliqués pour tous les PNR et ce, dans toutes les cours de justice au Canada.

Conséquemment ces gouvernements, en n’assumant leurs devoirs envers les PNR, engagent leurs responsabilités pour tous les dommages causés par leurs négligences graves envers le respect des droits et intérêts de ces PNR depuis 2006 ou à tout le moins depuis 18 avril 2017, date à laquelle la Cour suprême du Canada a souscrit aux principes mentionnés précédemment.

Pour résoudre cette impasse, plusieurs solutions sont possibles. Il y a d’abord la mise en œuvre d’un recours collectif contre les gouvernements du Canada et du Québec pour tous les dommages découlant de la non possibilité pour les PNR de pouvoir défendre adéquatement leurs droits et intérêts dans les différents tribunaux dont ils ont la charge.

L’autre solution serait d’entreprendre des actions de nature politique de façon à faire modifier les lois afin d’obliger les intervenants du système judiciaire à appliquer concrètement les principes sanctionnés par la Cour suprême du Canada en 2017. Ainsi, les élections fédérales d’octobre 2019 serait une excellente occasion pour faire modifier la loi des juges de façon à les obliger à respecter ces principes sous peine de sanction.

…

Do Self-Represented Litigants have a Right to Justice outside Small Claims Court?

By Yves Montplaisir, Self-Represented Litigant (SRL)

I would describe myself as a relatively fortunate citizen despite the major problems and difficulties I have encountered over the last ten years. I have two wonderful children to whom I wish to leave a society in which they are able to seek justice, even if to do so, they need to represent themselves in front of a judge. Fortunately, we are probably among the rare inhabitants of this planet for whom this dream is possible, which is why I believe it is our duty toward future generations to start now!

The following text describes the lessons I learned following my experience at the Superior Court, the Quebec Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court of Canada for two individual cases of civil and professional liability.

In the first case (#500-17-091770-159), I oppose my financial institution, Caisse populaire Desjardins, my former personal notary and six real estate brokerage agencies. In the second case (#500-17-097489-176), I similarly oppose a real estate broker and his real estate agency in addition to a notary. It is important to note that the lawyers representing the notaries and brokers are the same in both cases since they are paid by professional insurance funds (the Quebec Real Estate Brokerage Professional Liability Insurance Fund (FARCIQ) for the brokers and the Quebec Notary Chambers Professional Liability Insurance Fund (FARPCNQ) for the notaries).

Rule of Law for All?

The title of this article implies a question: Do we live in a society where the rule of law in civil matters exists for citizens without lawyers or does it only exist for society’s richest who can afford to be represented by well-paid lawyers?

The title of this article implies a question: Do we live in a society where the rule of law in civil matters exists for citizens without lawyers or does it only exist for society’s richest who can afford to be represented by well-paid lawyers?

Before the July 17, 2017 judgment accepting the motion to dismiss the Caisse populaire Desjardins and my former notary, I believed, like most do in our democratic society, that I had the right, under the law, to undertake legal proceedings myself without a lawyer.

I believed that all judges at hearings were impartial, fair, attentive and sensitive to the consequences of abuse or misconduct that I may have suffered from a third party. I also believed that judges would make up for any procedural inconveniences resulting from an SRL’s lack of knowledge of the proceeding in order to maintain the balance of power between the parties; this would ensure a fair debate to bring out the truth and the resulting right. I believed that a judge would take into account my constraints so that I could have the time I needed to properly assert my rights and represent my interests.

With the exception of a few judges, this is unfortunately not my experience so far in the Superior Court, the Quebec Court of Appeal and even the Supreme Court of Canada. I am therefore obliged to answer no to this question. Therefore, a SRL in Quebec cannot in practice exercise his or her right to justice in the current superior courts of justice.

Who are these judges and where do they come from?

I also realized that these judges are often lawyers coming from large law firms where they were well-paid, at least $200,000 per year, by multimillionaire if not billionaire clients and that I was attacking the kind of clients that had allowed them to get rich.

As a SRL I was engaging in legal proceedings in which, in their opinions, only lawyers had a reasonable chance to succeed and only lawyers such as themselves should have the right to partake. Therefore, giving reason to a SRL is to confess that it is not necessary to gain the skills of a lawyer, denigrating the value of their own skills as a lawyer. As a result of these prejudices and conflicts of interest on the part of the judges, it becomes impossible in practice for a SRL such as myself, from the onset, to have the chance of success.

Additionally, as a SRL, if the judges were to side with me, awarding me millions of dollars in damages without having needed to hire a lawyer, what would become of lawyers and the value of their high fees in front of an army of SRLs in the courts of justice to claim, like me, respect for their rights?

Thus, how could lawyers from large law firms convince their wealthy clients to pay them exorbitant fees if they cannot guarantee that they will not have to pay against a SRL, even if those wealthy clients are at fault? How could these lawyers give this assurance without being certain that the majority of judges that come from the same large law firms as them will not award significant damages to a SRL?

By becoming judges in the Superior Courts, lawyers from large law firms bring with them the legal culture and prejudices against SRLs alongside a desire to maintain the current legal system. This is the only logical explanation to justify the behaviour and decisions of some of the judges I met in my cases. Thus, lawyers, whether litigators or judges, have a conflict of interest when it comes to allocating resources and support to SRLs because SRLs are seen as competitors who threaten the profitability of their profession and their exclusive control of the justice system.

Does the Pintea v Johns judgment provide a framework for the discretionary power of judges?

Through my experience in the Quebec courts, I have come to realize that the discretionary power that judges have can be exercised in a completely arbitrary manner, without logic to the facts, evidence presented, laws and precedent invoked by a SRL.

This is why I was pleased when the Supreme Court of Canada in Pintea v Johns(April 18, 2017) undertook the framing of this discretionary power by outlining the principles in the Canadian Judicial Council’s Statement of Principles on Self-Represented Litigants and Accused Personsdeveloped in 2006:

- PROMOTE THE RIGHT OF ACCESS by ensuring that all SRLs can understand and effectively presenttheir case by having access to open, transparent, clearly defined, simple, convenient, effective, easy-to-understandcourt processes, that they haveadequate self-help support, that they are made awareof the implications and responsibilities of not having a lawyer, and that they are directed to other appropriate sourcesof information, education, advice and assistance;

- PROMOTE EQUALITY OF JUSTICE by ensuring that all SRLs have equal access to a justice systemwhere the judicial process is fair and impartial, SRLs are not unfairly disadvantaged, SRLs are not prevented from obtaining redressdue to a minor or easily correctable flaw in the presentation of their case, judges use case management measures as needed to protect the rights and interests of the SRL, and judges use non-detrimental and positive case management and courtroom management measures to protect the equal right of the parties being heard; and

- ENSURE THAT ALL JUDICIAL PARTICIPANTS such as judges, lawyers, administrators, other participants in the justice system and the SRL assume their responsibilitiestowards the proceedings initiated by the SRL.

Accordingly, judges must apply these principles in all of Canada’s justice systems when one party is a SRL. These principles are in addition to those principles that are applied to all parties, as enacted by the Canadian Judicial Council in the Code of Judicial Conductfrom 1988 which includes independence of the judiciary, integrity, diligence, equality and impartiality.

What are the indicators that may enable us to assess whether a judge, at a hearing or in his or her judgment, respects the principles upheld by the Supreme Court of Canada in Pintea v Johns?

There are, between my own and others’ experiences, certain questions that can indicate whether the principles upheld by the Supreme Court of Canada are respected during a hearing or judgment in which a SRL is present:

- Did the judge question the SRL about the a priorireasons or facts likely to influence his or her decision?

- Before rendering a decision, did the judge describe his or her reasoning in a detailed and transparent manner to the SRL?

- Before rendering a decision, did the judge explain to the SRL why he or she intends to use certain grounds in the preparation of his or her decision?

- Was there a reasonable opportunity for the SRL to correct the errors of reasoning and fact that are part of the judgment’s reasoning logic?

- Is there, in the reasoning of the judge, an assessment of the legal factors (Charters, Laws, case law, etc.) that may be favourable to the SRL’s case and evidence of the assessment of the balance of probabilities?

- Was there a reasonable opportunity for the SRL to effectively prepare and respond to the reasons given by the judge before the judge rendered his or her decision?

- Was any accommodation offered to the SRL so that he or she could have more time to find an expert since it is very rare for an expert to accept a warrant when he or she has no lawyer on file?

- When the SRL failed to find the expert he or she was looking for within the prescribed time, did the judge assess the possibility of imposing a common expert in search of the truth and resulting right?

- Has the judge read and examined all of the documents and evidence submitted by the SRL?

- Has the judge provided the SRL with the additional assistance required, adapted to his or her medical, family, professional, legal, and other constraints which limit his or her possibilities of action?

- When noting a weakness in the SRL’s case, did the judge correct this weakness or procedural error?

- Did the judge set deadlines that respect the constraints of the SRL?

- Throughout the proceedings, did the judge ensure that the counsel for the opposing parties did not mislead or deceive the SRL, especially when preparing to make a decision unfavourable to the SRL?

- Did the judge ensure that the lawyers of the opposing parties properly assumed their obligations to the SRL as an officer of the court?

- Did the judge ensure that the lawyers of the opposing parties properly complied with their ethical obligations to the SRL?

- Has the judge ensured that the SRL truly enjoys a full and fair debate?

- Did the judge question the SRL so that he or she could assess the relevance of possible favourable and unfavourable reasons toward the SRL that could be used in his or her decision?

These questions are particularly relevant when it comes to comparing and understanding two similar judgments involving the same SRL with two opposite results.

I discovered these indicators, in the form of questions, when I sought to understand why on the one hand, I had failed to prevent the trial judge’s acceptance of a motion to dismiss the case requested by my financial institution, Caisse populaire Desjardins, and the Quebec Notary Chambers Professional Liability Insurance Fund (where the Quebec Real Estate Brokerage Professional Liability Insurance Fund was in question) and, on the other hand, the refusal of the same motion to dismiss by another trial judge of the same Superior Court in another case where the other parties were also the Quebec Notary Chambers Professional Liability Insurance Fund and the Quebec Real Estate Brokerage Professional Liability Insurance Fund.

Obviously these indicators are not exhaustive and there are surely several others that are not mentioned. That is why I asked the Supreme Court of Canada to confirm or refute these indicators and to define others as needed to ensure that all Canadian SRLs have simple and effective assessment tools to determine whether or not a judge is respecting the principles that the Supreme Court of Canada upheld in Pintea v Johnsand thus put an end to the arbitrary and discriminatory behavior and decisions of some judges towards SRLs.

Unfortunately, the Supreme Court of Canada refused to uphold the principles that it affirmed in Pintea v Johns. The Court refused my appeal in a case where the evidence of non-compliance of these principles, of discrimination and of fabulation on the part of the trial judge of the Superior Court are numerous and clear, and further that the Quebec Court of Appeal has twice refused to correct, Quebec SRLs have reason to doubt the ability of a large number of judges to be able to provide justice to an SRL.

How to guarantee the respect of an SRL’s rights?

If current courts are overwhelmingly hostile against upholding the rights and interests of SRLs, who has the power and duty to correct the situation and ensure that an SRL’s rights and interests can be respected and defended at all times?

Who has the power and duty to appoint these Superior Court judges and to define the criteria for appointment so that the rights and interests of SRLs are respected?

Who has the power and duty to ensure and assess whether judges are respecting their obligations to SRLs?

Who has the power and duty to train judges on an ongoing basis in how to fairly intervene with a SRL?

Who has the power and duty to periodically assess the respect of the principles and ethical rules that all justice system actors must uphold in the presence of a SRL?

Who has the power and duty to correct the behavior of those in the judicial system that may not respect the principles and ethical rules that must be upheld in the presence of a SRL?

The answers to these questions show us that the governments of Canada and Quebec have the ultimate responsibility of ensuring that the principles enumerated by the Canadian Judicial Council in 2006 apply to all SRLs in all courts of justice in Canada.

Subsequently, by not fulfilling their duties towards SRLs, these governments bear the burden for all the damages resulting from their serious negligence towards the respect of the rights and interests of SRLs since 2006 or at least since April 18, 2017, which is when the Supreme Court of Canada upheld the above-mentioned principles.

There are several possible solutions to resolve this impasse. First, there is a class action law suit against the governments of Canada and Quebec for all the damages incurred in their various courts regarding SRLs’ inability to adequately defend their rights and interests.

The alternative would be to take political action to change the laws in order to force the justice system to apply the principles upheld by the Supreme Court of Canada in 2017. Therefore, the federal election of October 2019 would be an excellent opportunity to change the law of judges to compel them to abide by these principles with a penalty of sanction.

Such a timely voice for me to hear! Thank you! I don’t want to jinx my chances, but so far my Supreme Court judge in bc has been accommodating. To the point of walking me through how to fill out a one page request to proceed. He has listened, asked questions to clarify, and approved of my submissions so far. The real proof will be in court again when I am before the mass respondents lawyers and I crumble from my ptsd. Thank you again!

You nailed it! Your thinking looks very similar to my thinking. Please look at my article/submissions at https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/complaint-canadian-human-rights-standard-content-nmla-konesavarathan-1e/ which discusses Standard of Impartiality in Canada at paragraphs 259-316 and The Flaws of Judicial Appointment in Canada at paragraphs 317-352.

While I describe it as a problem of judicial appointment process, you describe it as a problem of ‘Who are these judges and where do they come from?’ The solution for this common problem is to revise the judicial appointment process. We all should raise a unified voice to bring changes to the judicial appointment process.

My thoughts are that there should be completely separate Law Schools for Judge’s and Crown Prosecutors only. Located on Campuses separate from Law Schools for Lawyers!

Of course, we all have a different individual story. However, we should not let the difference of our stories divide us. Although our stories are different, the solution is the same – bringing changes to the judicial appointment process to ensure only impartial and competent individuals are appointed and retained as judges.

If we let less impartial and less competent individuals to be appointed and retained as judges, we cannot expect that these judges will consistently apply the law or what you mention as the framework provided in Pintea v Johns.

As you mentioned, the federal election of October 2019 provides an excellent opportunity to take political action and to bring changes to the law. Currently, no party is talking about any reform to our judicial system. Will we be able to convince at least a single party to commit to reforming our judicial system or at least the judicial appointment process?

The parties or their local candidates need just 30-40% of the votes to win in this First-Pass-The- Post election system. The major parties have already calculated where to get their 30-40% votes. They may pretend to listen to us but will not indeed have commitment to bringing reform to our judicial system. It is very important to find politicians, who are already passionate and committed to bringing reform to the judicial system, and to support them. In order to do that, we have to work together regardless of our individual differences.

I salute your critical and analytical thinking skills to arrive at 17 indicators to assess judges. Although the lawyers and judges portray themselves to have superior critical and analytical skills, we know, as a fact, that their submissions and decisions show that their critical and analytical skills are lower than an ordinary journalist. They use their legal training and title as a privilege to make inexperienced people believe that they have superior critical and analytical skills. Because of their feeling of insecurity or fear of losing their privilege, they are unable to recognize the superior skills of SRLs who are also educated and, truly involved and passionate in advocating for their rights.

Great piece ! It is a big problem for sure & here is a lot more proof of exactly what he says is true . Including how a judge has stopped a SRL cases from moving forward with the vexatious litigant scheme the judges has created , made up mistakes & not even a chance to go to court to explain my self !! This site has being cleaned up so let this reply be shown .

http://alberta.newjusticeforthepeople.com/vexatious-litigant-scam/

In my first appearance in a superior court as an SRL I didn’t perceive bias on the part of the judge (who had fairly recently been appointed to the bench), but the judgment in my favour was followed by a very stressful ongoing engagement with the three other parties (one being a tribunal) that culminated in a B.C. Supreme Court hearing that was a nightmare and that the registrar then told me hadn’t been recorded.

.

From that point onwards I was inclined to presume that whatever judge I might face was not capable of impartial adjudication, and the results continued to confirm that.

.

A couple of days ago I found on the website of the Canadian Institute for the Administration of Justice three PowerPoint presentations from a “Roundtable” about vexatious litigants. Go to this link – https://ciaj-icaj.ca/en/library/papers-and-articles/roundtables/ – and click on the entry for March 10, 2016.

.

Grant Lester, an Australian, was one of the driving forces behind the campaign to build a comprehensive rhetoric about vexatious and “querulent” litigants. A rhetoric to which the Canadian legal establishment has been very receptive.

.

Freya Kristjanson was appointed to the Ontario Superior Court of Justice just three months after presenting at that Roundtable. Her 35 page presentation ends with a footnote referring, with approval, to Justice Yves-Marie Morissette’s speech that I believe the Canadian Association of Counsel to Employers removed from it’s website in response to my criticism of it.

Correction – it was the B.C. Court of Appeal, not the B.C. Supreme Court, that held the hearing I was told hadn’t been recorded.

I wonder how many plaintiffs (with a lawyer and SRLs) have had their drawn-out cases killed due to a “judicial error” at the Court of Appeal stage. Essentially, the Court of Appeal in each province is the last resort because of the roughly 16% of applications for review each year that are accepted by the Supreme Court of Canada, the majority of the 16% pertain to criminal cases.

It’s also hard to fathom that there are still a few provinces whose Court of Appeal will not allow an appellant a copy of the transcript of the appeal hearing. You can request from the 3-justice panel a transcript, but you will be refused. If that is the case, how can you ever inform the Supreme Court of Canada in your application that you felt the Court of Appeal majorly screwed you when you have no transcript of the appeal hearing? The Court of Appeal’s written decision naturally will not mention the appellate judges’ inappropriate conduct, bias, cuss words, racial profiling, laughter/mocking, etc.

Have you all noticed the humorous idol worship of judges throughout Canada? I am referring to judges (Superior Court, Court of Appeal and Supreme Court of Canada) no matter if they’re currently sitting, retired or just recently deceased. Lawyers will postpone planned family outings just to get to the venues early to sit, listen and adulate the judges who will be speaking (hanging onto dear life to each word) or will be honored. They will address them as the Honorable Ralph G. Scott or my Lord/my Lady with their heads bowed.

Currently, a group of Supreme Court of Canada justices who are making a cross-Canada tour of major cities in order to reach out to Canadians and lawyers everywhere are packing the meeting venues to the rafters.

Hi everyone,

Thanks a lot for your comments. You are all right regarding the problems encountered by SLRs across Canada. It’s about unrespect of our fondamental right to access to civil Superior courts.

In these courts, People think that if they go to court like SLRs, the judges will help them to obtain justice but it’s rarely the case. And one day if you are lucky with one judge, the next days the SLRs can loose evetything with an other judge.

In fact I think, SLRs need a Guide to access to justice written by SLRs explained with thru cases.