The Law Society of Ontario is responsible for regulation of the professional conduct, competence, and capacity of Ontario’s lawyers and paralegals. The LSO believes it handles complaints in a timely, open, and efficient manner and adequately balances the public’s interest and its licensees’ interests.

As a member of the public who has used the LSO Complaints system, I have a different opinion. I found that the processes were opaque and unresponsive, and that both the processes and the outcomes were heavily biased towards lawyers. The LSO may attribute my complaints as one person’s experience, and a disappointing decision as being my subjective interpretation, but my criticism of their processes is borne out by data.

Intake and Investigation

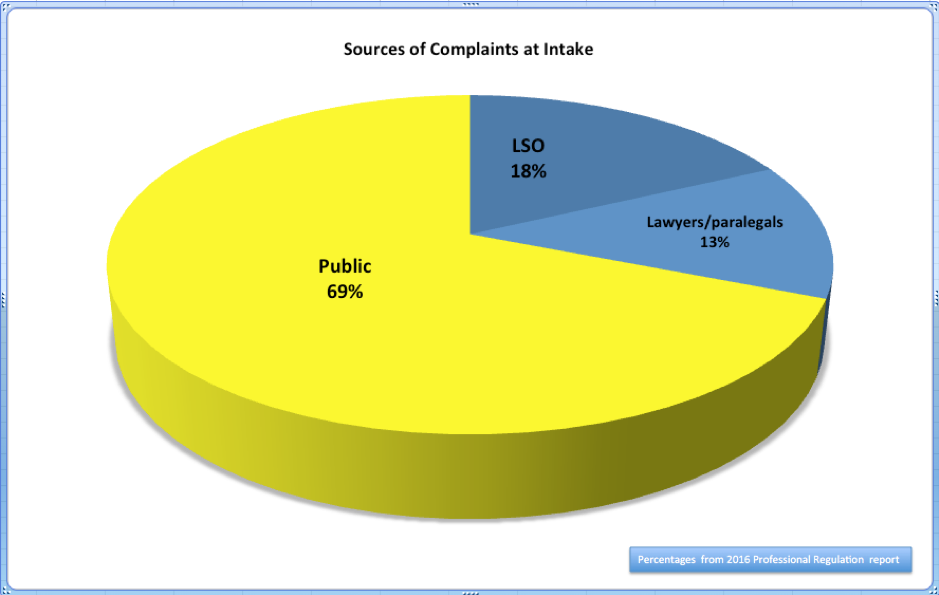

The Sept 2016 Professional Regulation Committee reports (presented at the Feb 2017 Convocation) that 69% of complaints come from the public, 13% from licensees (lawyers), and 18% are generated by the LSO itself under s49(3) of the Law Society Act. In 2018, they report that there were 6,500 complaints at Intake (Part 1 of the process), of which 1,200 were referred for Investigation (Part 2 of the process).

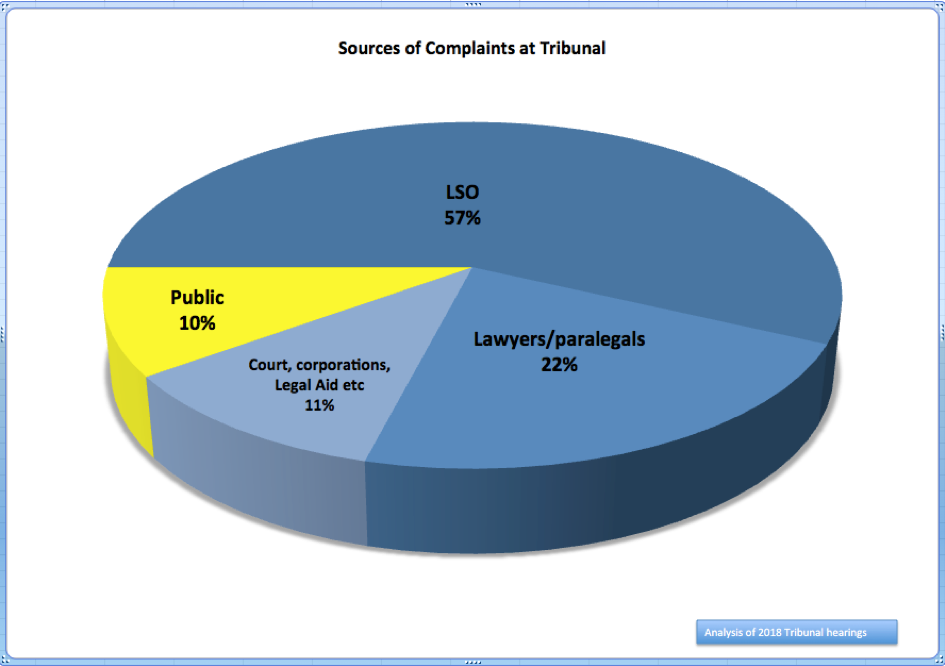

The raw data suggests that a complaint has a 1 in 5 chance of surmounting the hurdle for investigation, which would be true if all complaints were treated equally. However, an analysis of the tribunal hearings suggests that public complaints are disproportionately culled in the Intake and Investigation assessments, just as SRL actions are more likely to be dismissed before reaching trial.

The LSO doesn’t actually provide any data on the number of public complaints (among the 1,200 referred to the Investigations phase), or the number of public complaints referred to the Proceedings Authorization Committee (Part 3 of the process). However, if you are willing to pore over and tabulate the 166 tribunal findings (Part 4 of the process) for 2018 (and I did), then you find that only 10% of complaints reaching the tribunal originated from a member of the public. It is reasonable to interpolate that this percentage will be typical for investigations overall. SRLs as a fraction of the public would represent an even smaller percentage.

Timeliness and Responsiveness

The National Discipline standards of the Federation of Law Societies state that 80% of complaints against lawyers should be resolved or referred for disciplinary follow-up within 12 months, rising to 90% within 18 months. In 2018, the LSO was just shy of these targets, at 76% and 86% respectively. This was an improvement over previous years, and the result of the LSO hiring more staff in 2016 and changing their processes so that the Intake department closed 11% more complaints and transferred 24% fewer complaints to Investigation in 2016 than in 2015. These process changes mean that more complaints are closed without an investigation. The Law Society’s Complaints Resolution Commissioner cannot review these decisions.

The LSO’s non-compliance with the National Discipline standards target of contacting the complainant at least once every 3 months for 90% of open complaints has been addressed in a similar fashion. In 2017, the LSO only met this target for 68% of complaints. Rather than ask Investigations staff to diarise their cases and provide the status update to the complainant, the LSO has proposed that the Federation adjust the standard to require contact every 5 months – a target which the LSO currently achieves only 78% of the time. In a similar fashion, the LSO has proposed relaxing the benchmark requiring contact with the lawyer/paralegal who is the subject of an open complaint from 3-month to a 5-month interval; a change which improves the LSO’s compliance from 57% to 73%. (See https://lawsocietyontario.azureedge.net/media/lso/media/legacy/pdf/c/convocation-professionalregulationcommitteereport-may-2018.pdf at pages 5, 6, 16 & 17.)

My complaint

In February 2015, I complained that the lawyer representing my elderly uncle and aunt had acted against the interests of my uncle, and that there was a serious risk that her behaviour could adversely affect other elderly and vulnerable clients. The wills she had written for my aunt and elderly Alzheimer’s-affected uncle effectively disinherited him. After my aunt’s death, the lawyer wrote powers of attorney for my uncle which appointed the trustees for my aunt’s estate. She then assisted the trustees in their efforts to move my uncle into long-term care, against his express wishes. Additionally, as the lawyer for the estate trustees, she followed their direction to use $80,000 from my aunt’s estate to pay the expenses of my uncle’s estate – including litigation fees – an action that enriched the trustees. These misappropriations amounted to more than 1/3 of the estate and were documented using copies of the lawyer’s own trust accounts.

The LSO Intake section promptly referred my complaint to Investigations where it disappeared into a Black Hole. Every 3 months I emailed asking for an update. For 18 months, the reply was that my complaint was still being read. I tried contacting the Investigations supervisor and the Profession Regulation manager, but couldn’t because the LSO doesn’t provide contact details for these positions. Eventually, I contacted the Chair of the Professional Regulation committee via his work email. This resulted in a short period of activity before the complaint again languished in a pending tray. After 19 months of being told the complaint was still being “read”, I contacted the Hamilton Police. Another flurry of activity resulted, and then in November 2017, 33 months after I lodged it, my complaint finally reached a Step 3 Regulatory Meeting.

At the Regulatory Meeting the Proceedings Authorization Committee found that the estate lawyer had not properly checked for capacity and had acted where she had a conflict of interest. It also found that she should not have used money from one trust account to pay the expenses of another without permission from the beneficiaries. The committee concluded that the discussions had been useful, and that the lawyer was unlikely to act this way again. I found this response underwhelming.

Priorities

The professional conduct of cases involving elderly and vulnerable clients seems to me to be an important priority for the legal profession. I felt that the LSO did not address the lawyer’s behaviour in a timely manner, and even sent a conflicting message since, throughout the investigation, the lawyer was a regular presenter at accredited Continuing Professional Development trainings in the areas of practice for which she was being investigated. I raised this with the LSO several times, since I felt it gave the impression that the LSO was endorsing her expertise in these areas, but the LSO did not share my concern.

In contrast, in 2018 the following cases were allowed to advance to part 4, a tribunal proceeding:

- A complaint about incivility where a muttered obscenity was picked up by the court microphone. The tribunal hearing occurred 9 months after the date of the incident.

- A complaint about misleading advertising which claimed that the use of “golden” in the firm name suggested “qualitative superiority to other lawyers”.

Types of Complaints

My breakdown of the 2018 LSO Tribunal proceedings shows that the largest single complaint category was “failure to co-operate with an LSO investigation”, which accounted for 42 of the 166 hearings. Many of these cases originated from public complainants, and 1/3 of them involved multiple complainants; however, the hearings did not address the substance of the alleged unprofessional conduct, but rather the failure to co-operate with the LSO. Other actions initiated by the LSO included 9 misleading advertising concerns, 12 motions for costs arising from the discipline process, and actions about incivility, administrative suspensions, license reinstatements, fraud/misuse of funds, and requests for interlocutory suspension where criminal charges had been filed or found.

I identified only 17 complaints at the Tribunal level which appeared to have originated from members of the public, and did not also include additional support of a criminal charge, police finding, or a complaint from a lawyer, Legal Aid Ontario, or other legal body. Only one hearing included a complainant who was an identifiable SRL, and Legal Aid Ontario was one of the other complainants in that matter. 4 of the 17 public complaints had between 10 and 38 complainants, and raised issues of misuse of funds or mortgage fraud (Law Society of Upper Canada v. Fine, 2018 ONLSTH 56, Law Society of Ontario v. McEnery, 2018 ONLSTH 83, Law Society of Upper Canada v. Savone, 2018 ONLSTH 39, Law Society of Ontario v. Low, 2018 ONLSTH 1020). It is reasonable to assume that SRLs were amongst the parties in these 4 complaints, but it is not possible to be certain from the decision.

In summary, the LSO Complaints process disproportionately addresses complaints by lawyers about other lawyers regarding matters of interest to lawyers.

Anne Rempel has been dealing with the self-regulatory complaint systems of hospitals, the HNHB-CCAC, and the CIBC regarding elder neglect and financial abuse concerns since 2012. She has been raising similar issues with the LSO complaints system since 2015. NSRLP has been provided with a copy of her 2018 Tribunal analysis spreadsheet.

The problem is simple. LSO owns the lawyer insurer, LawPro, and if they find against any lawyer, LawPro will have to pay out. Corporations are corporations are corporations — all about profit. LSO is not going to shoot itself in the foot by finding against a lawyer.

The Code of Professional Conduct is clear…a lawyer who has failed to meet his obligations under the retainer, missed the limitation period, etc, must return the fees quickly without putting the client through more hell. But like the Charter, the Code is pure rhetoric and not worth the paper it was written on.

The Courts have been clearer — where a lawyer has missed a limitation period or where the client received no value at all, the lawyer was not entitled to collect fees.

But LawPro runs a parallel system of Court Rules and I can prove this without any shadow of doubt.

In fact, I recorded a Deputy Judge stating that they were a ‘special entity’ in order to excuse a 16-week delay in filing Defences, refusal to say a word at a mandatory settlement conference, and dealing with a Motion to Strike their Defence not by Responding with law, but instead by bringing a Motion to Dismiss, with no law or no justification argued as a means of alerting the Deputy Judge to what LawPro wants.

No matter how clear the case, LawPro will drag it out for years, misrepresent information and direct the Judge (in my case, the Deputy Judge) as to why they want and they get it.

In another case against the same defendant lawyer, LawPro put off the Statement of Defence for two years so after providing several indulgences, I had the Registrar note them in default.

Sure enough, LawPro has brought a motion to set aside the note in default and you can bet your next paycheck they will have the note in default set aside.

Self-regulation does not work. Allowing lawyers to run everything in society works even less. They have destroyed communities, families, marriages and life in general. They have destroyed Canada.

On the one hand the Law Society is supposed to protect us from the illegal and inappropriate conduct of their members by holding them to account when complaints are filed. On the other hand the Law Society is to advocate, protect and serve the interest of their members. This presents itself as a conflict of catastrophic proportions that simply cannot be overcome. The evidence that the Law Society complaint review process is not working is overwhelming in the sheer numbers of complaints that either go nowhere or end with findings that protect the wrongdoing and illegal conduct by the Law Society members.

Sufficient pressure must be brought to bear so that a new complaint review process is developed. A complaint review process in which complaints are dealt with and ruled upon by independent third party reviewers that the Law Society holds no sway over.

Dear Anne, how dreadfully dad for you and your Aunt and Uncle! I am sad to say this happens in British Columbia too. I was managed the same way by the bc law society over a conflict of interest case against a very high profile lawyer. The law society determined that his only fault was in not properly telling his ptsd client that she had no chance of winning her wcb claim. The law society felt he would not make this same oops again, the end.

Thank you so much for your research in bringing those numbers to light! I will be referring to them! Lorelei

Hi Lorelei

There was a happy ending for my uncle; he stayed in his home. My sister and I contacted a lawyer who told us that our uncle’s wishes took precedent over the wishes of his Powers of Attorney, and guided us through the legal steps to make that happen. We were fortunate that we could afford to go this route; most people wouldn’t have this option.

.

I complained to the Law Society because I didn’t want the lawyer to repeat her behaviours with another family. My complaint specifically stated that I thought the matter could be resolved through discussion and education- and the LSO claims that this is what they did. I am sceptical about this since I had to badger the LSO for almost 3 years to get any action.

.

In the end the LSO Regulatory Meeting concluded “that the discussion was useful, and that the Lawyer is unlikely to conduct herself similarly in the future”. I think a better summary would be that ‘it is unlikely that the next family will have the documentation required, or the persistence, to get their complaint through the LSO process’.

What’s the news here? Anyone who has attempted to access this system in any province can attest to its miserable record of fair and impartial representation.

Lawyers need to be held more accountable. I have an appointment with one and I must pay in full, in advance, for the 90-minute consultation—which cannot happen for more than one month, due to this litigator’s holiday schedule.

The fee?

$975 before taxes plus fees . . . that’s $10.83 each minute of discussion, including my own chatter and time looking up legal questions they cannot answer . . . and all for the same patter: “there’s no guarantee of outcomes.”

Professionals making that kind of money need to have their feet held to the fire, always, with no excuses and receive maximum punishment when they make an error of any kind.

They also need to be made to offer substantial pro bono services to the public; I’d suggest 10% of their gross income each year. That’s what churches used to charge for tithes and it seems reasonable for such gross money-making in a field that “obfuscates, inveigles and deceives” to make its money.

This is equally as thoroughly researched and well-written as it is damnifying against the LSO. Well done Anne!

.

I will add that my understanding is a failure to “cooperate” is sometimes (often?) used as an easy out for both the lawyer and the society. In particular, failing to cooperate means Lawpro (the insurance program) can use that excuse to deny representation and third-party liability coverage to the lawyer in the event of a suit for damages for misconduct. The lawyer and Lawpro can then more easily evade the suit and collection of any judgment award, and are happy to let the sleeping dogs of outrageous misconduct lay quietly.

.

It is an oxymoron to say ‘justice system’ in the context of what currently exists. It is just a system that works for the lawyers, however high up they sit.

Same problems in Alberta . The law Society protecting the Lawyers & threaten the complaints to not put any of their documents on a website ?? All under cover . The end of self regulation must come to an end ASAP. See what I mean . http://alberta.newjusticeforthepeople.com/greg-weber/ and here

http://alberta.newjusticeforthepeople.com/how-the-law-society-works-for-the-lawyers-and-not-the-people/

In my case, I am an SRL (self-represented litigant) who’s dealing with a lawyer who chaired the 2011 revisions to The Law Society of Manitoba’s Code of Professional Conduct. He was also the opposing lawyer of the defendants (my two former lawyers) I was suing for legal negligence. The Law Society of Manitoba’s Insurer was paying him to defend against me.

On April 27, 2016, I emailed him saying that I was going through a divorce and also contemplating filing for personal bankruptcy. I was NOT seeking his advice, but he advised me anyways to see a trustee (and not a bankruptcy lawyer- in fact an opposition lawyer should never give advice to an SRL which is unethical conduct) saying “Mr. SRL, when you meet with a Trustee in Bankruptcy, you will want to advise him of this action. He can give you advice on what happens to personal lawsuits in a bankruptcy situation.”

So I did what this opposition lawyer advised me and the following year when I filed another lawsuit against another of my former lawyer for legal negligence, he filed a Notice of Motion to Dismiss my Statement of Claim saying that because I was a bankrupt, I had no legal authority to continue my existing lawsuit and also to begin this new action due to my assets being vested with my Trustee. He won the motion in both the Queen’s Bench and Court of Appeal.

In essence, he set me up!

I complained to the Law Society of Manitoba’s Discipline Committee which dismissed my complaint against him.

In the USA, lawyers MAY insure themselves against being sued by clients/former clients for legal negligence through any private insurance companies that offer professional liability insurance.

In Canada however, all lawyers must pay annual premiums to their Law Society’s “owned” insurer (which is a blatant conflict of interest) and not to any private insurers. It’s a monopoly! Canadian Law Societies boast on their websites how such insurance protects the public. Yeah, right!

So when the public sues their lawyer/former lawyer, the Law Society through its “owned” insurer provides a lawyer (usually a Law Society bencher) to vigorously defend him/her. The same goes for any complaints against your lawyer/former lawyer. The Law Society’s Discipline Committee would not sanction/discipline a fellow lawyer (who’s a bencher or someone who worked for them in the past) for misconduct. They might say that his conduct was part of his litigation strategy that is exempt from discipline.

First, excellent blog and some excellent responses. I am currently at the ‘appeal’ stage with my matter and it’s been about 7 months. I hope to share with you once I get a response. I assume most of you know it is important to be squeaky clean when submitting a complaint to the LSO. The LBO gets about 3000 complaint letters a year (Google search) . They are probably overwhelmed.